History of the Crete State

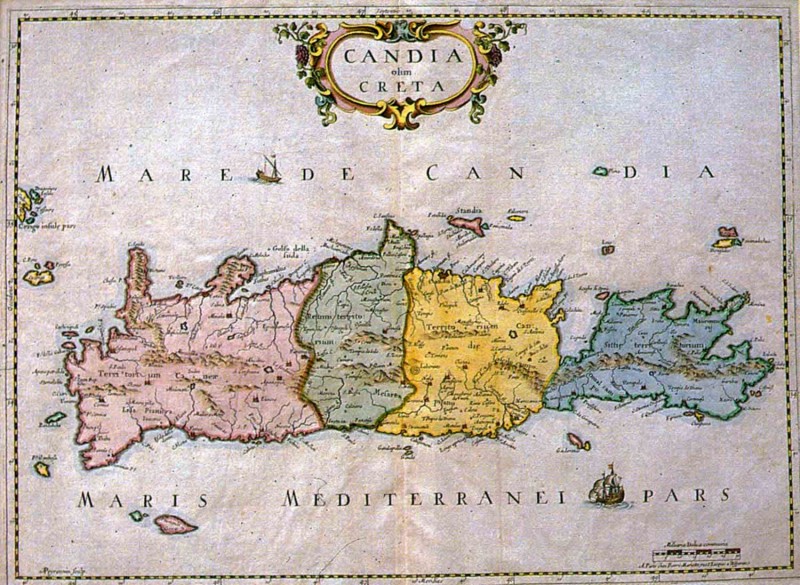

War of Candia

In the middle of the XVII century the island of Crete was the largest and richest overseas possession of the Republic of Venice. It was located almost in the center of the Ottoman Empire’s interests: at that time, it reached the highest point of its influence. But Crete was of considerable strategic interest not only to the empire but also to the Republic of Venice, and the war for Crete between them was inevitable.

The formal reason for the attack on Crete was the capture by Christian pirates—knights Hospitaller—of Muslim ships with Turkish pilgrims. We wrote about this earlier: in the archive of the newspaper you will find the article “It seems that a person caused the conquest of Crete was a Russian”. Pirates landed in Crete for a very short time. However, this landing caused the declaration of war on Venice and the subsequent landing of Turks on the island.

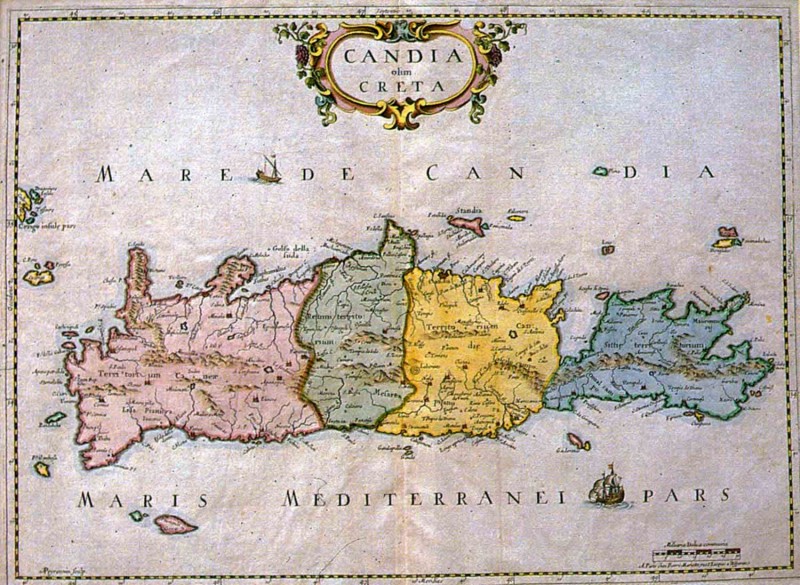

The Cretan war, also known as the War of Candia, began in 1645 and lasted more than 20 years—until 1669. Almost the whole of Crete was occupied in the first years of the war, but the capital of Crete, Candia (present-day Heraklion), resisted the Ottomans for a very long time—21 year. The riots in the Ottoman Empire and the war in Europe did not allow the Ottomans to quickly win. A long siege of Candia forced the parties to transfer the main hostilities at sea. The Venetians, real merchants, hoped for the depletion of enemy reserves, so they tried to block the supply of the Ottoman troops, which was carried out by sea. During the war, the Venetian Republic had a general superiority at sea, but even it was not able to completely block the Ottoman supplies and reinforcements to Crete. The protracted conflict drained the economy of Venice, which was based on trade with the East through the ports of the Ottoman Empire; and in Venice there was some fatigue related to the war.

The Ottomans, having managed to gain a foothold in Crete, sent in 1666 a large expedition led by the great vizier himself. The last phase of the siege of Candia began and lasted more than two years. The city capitulated. Venice was forced to sign a peace treaty. The capital of Crete costed the Turkish army 130 thousand people. During the siege were killed 30 thousand Greeks and Venetians. Crete was transferred to the Ottomans on September 16, 1669. The island of Gramvousa, the fortress of Suda and the fortress island of Spinalonga remained with Venice. These three fortresses protected trade routes of Venice, and were also strategic bases in the event of a new war with the Turks.

The surrender of Candia put an end to four and a half centuries of Venetian rule in Crete. Venice lost its largest and most prosperous colony, its trade position in the Mediterranean has worsened. Fifteen years later, Venice, seeking revenge, started a new war (Morea War, 1684–1699). During it, the Venetian fleet attempted to recapture Candia, but failed. Spinalonga and Souda were conquered in 1715 during the Peloponnesian campaign against Venice; and Gramvousa was captured by the Ottomans in 1692.

At the same time, the losses suffered by the Ottoman Empire during this long war greatly contributed to its decline during the late 17th century. Crete became an Ottoman province and remained under full Ottoman control until 1897, when it received the status of an autonomous state under nominal Ottoman suzerainty.

Liberation struggle in Crete

In the Ottoman Empire, Christians were discriminated. Therefore, in Crete, many locals were forced to convert to Islam. At the same time, Cretan Muslims preserved the Greek language and customs. On the island, crypto-Christianity (the secret practice of the Christian faith) was widespread. In 1821, when the Greek War of Independence– sometimes called the Greek Revolution (1821-1832)–began, there were approximately equal numbers of Muslims and Christians in Crete.

Despite Islamization, Crete, like all of Greece, always strove for independence. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Europe was swept by a wave of revolutions. Turkish authority was weakening. In Greece, a national upsurge began, which met the support of Western European countries. After the Greek Revolution, which ended in 1832 with the Treaty of Constantinople and established Greece as an independent state, the Kingdom of Greece, Crete remained under Ottoman rule for a long time.

The Christians of Crete revolted with mainland Greece during the Greek Revolution. The uprising was brutally crushed, as, indeed, are all the others. About 60 thousand Cretans took refuge in free Greece. Unsuccessful uprisings in Crete in 1841 and 1858 failed to unite the island and mainland Greece, but forced the Ottoman authorities to make concessions to Christians. They were given the right to bear arms, proclaimed equality of religion. Councils of Christian elders have been created to administer education and have some judicial powers. The Muslim community was outraged by these changes, while Christians demanded further reform, considering unification with the Kingdom of Greece as their goal.

When several petitions to the Sultan remained unanswered, armed detachments were formed. A new uprising demanding enosis (union) with Greece began in Crete on August 21, 1866. This uprising went down in history under the name “The Great Cretan Revolution” (1866–1869). It found a great response in Greece and other European countries. The atrocities of the Ottoman forces caused a violent reaction after the assault on the Arkadi monastery, which housed the headquarters of the rebels and a significant number of refugees: when the Turks broke into the monastery, the rebels blew up the arsenal. There were significant casualties.

Crete—an autonomous state within the Ottoman Empire

In 1867, to resolve the situation in Crete, the Ottomans sent a commission there, led by the great vizier. The commission was in the island for several months. The Vizier not only crushed the rebellion, but also approved the Organic Law (limited constitution), which gave Cretan Christians control over the local administration.

Cretan-Christians rebelled against the Ottoman yoke over and over again, seeking to unite with Greece. Since 1875, a Revolutionary Committee was created in the island. The Cretans again took up arms in 1878, during the Russo-Turkish war. But the San Stefano Peace, which ended the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, did not provide for changes in the status of Crete, and the subsequent Berlin Congress determined that the island will continue to be Ottoman territory.

Under pressure from the European powers, the Ottoman government committed to undertaking administrative reforms to eliminate discrimination against the Christian population. This also applied to the case of Crete. As a conciliatory gesture, the Sultan first appointed a Greek Christian, Kostas Adosidis, as Governor-General (Vali) of the island. In 1878, the Halep Pact was concluded, according to which an autonomous state was formed in the island for the first time as part of the Ottoman Empire. An agreement was reached and signed between the Ottoman Empire and the representatives of the Cretan Revolutionary Committee, in the house of the journalist Kostis Mitsotakis (grandfather of the future Prime Minister of Greece and great-grandfather of another one) in Halepa (now the Chania region). The pact as a whole was carried out until 1889, when the Turks terminated it.

The termination of the pact led to another uprising in Crete in 1895–1898. This uprising received a huge response in Greece, whose government sent a small expeditionary force to reinforce the rebellious Cretans. On February 15, 1987, a one and a half thousand detachment of Greek troops landed under the command of Colonel Timoleon Vassos. Reinforcements by Greek volunteers also began. This uprising provoked the beginning of the First Greek-Turkish War of 1897.

Pressure from European states and failures at the front forced the Greeks to cease hostilities. This war was the only conflict between the Greeks and Turks in the 19th century, where Greece was forced to cede the land to Turkey (Thessaly). The military side of this 30-day war is completely insignificant. Politically, the outcome of the war, of course, raised the authority of the Sultan and the spirit of the entire Muslim world.

The great European powers intervened in the conflict and declared the island of Crete an international protectorate. In March 1897, a new autonomy was declared in Crete under the “patronage of Europe”, and in April about 3 thousand soldiers and officers landed in the island, sent by six countries: Austria-Hungary, Great Britain, Germany, Italy, Russia and France.

Establishment of the Cretan State

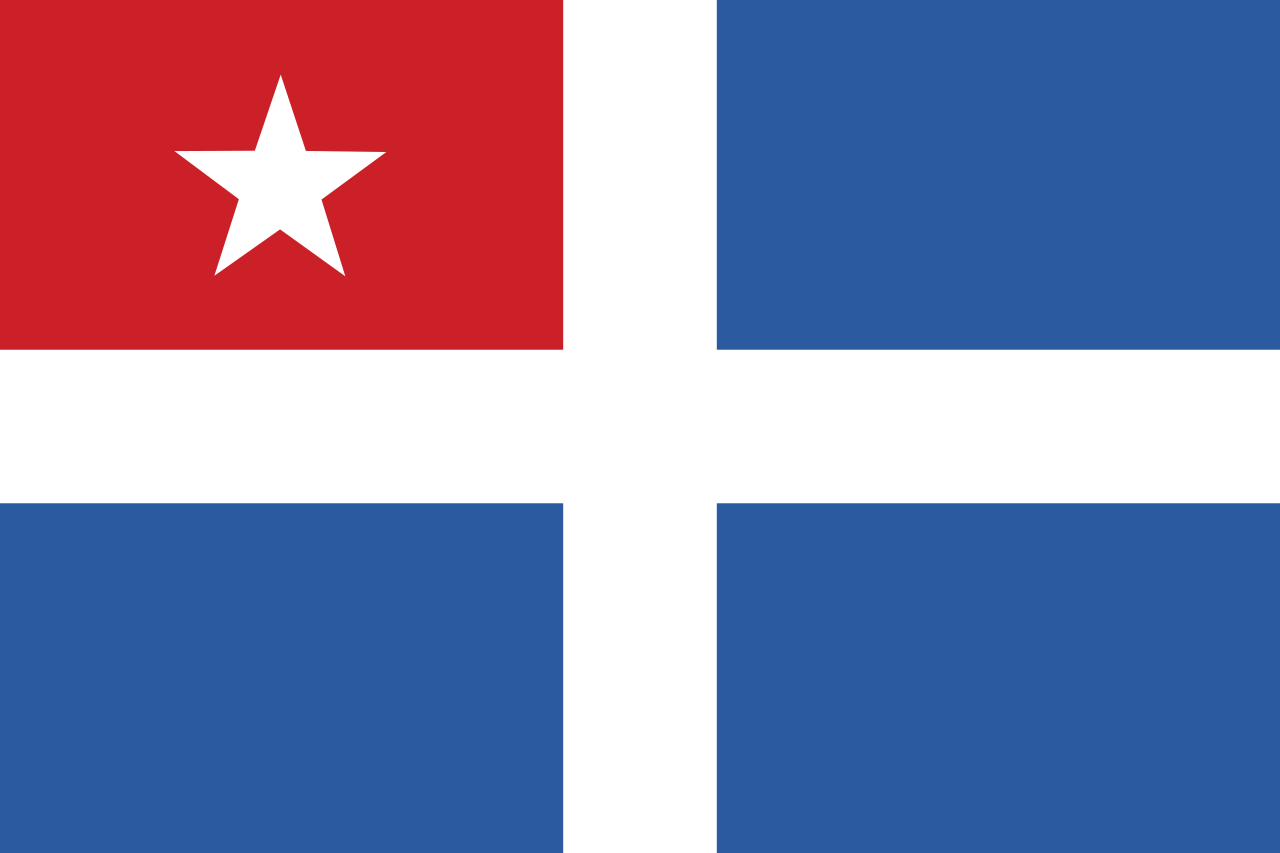

By March 1897, the great powers formed an interim government on the island–an “Admirals Council”, which consisted of four admirals and remained in power until the arrival of the Greek Prince George, the second son of the Greek king. Prince George was selected as the first High Commissioner.

In mid-1898, the Ottoman Empire made its last attempt to prevent separation of Crete. Jevad Pasha arrived in Candia, whom the Sultan appointed the Governor General. Soon he was removed to the post of Turkish forces commander in Crete. The repeated verbal clashes of Jevad Pasha with the “Admirals Council” of the European Powers forced the Ottoman Sultan in October 1898 to withdraw him. In September 1898, Turkish fanatics massacred local Greeks in Kandia. The British patrol, blocking the way to the rioters, lost one officer in a skirmish, 13 soldiers killed and twice as many were wounded. The British vice consul and several hundred Christians were killed. The riots were stopped only by the threat of the artillery bombardment of Candia. After that, the European powers forced the Ottoman Empire to begin the withdrawal of its troops. In 1899, the last Ottoman units left Crete. A significant part of the Muslim population of the island left it with them.

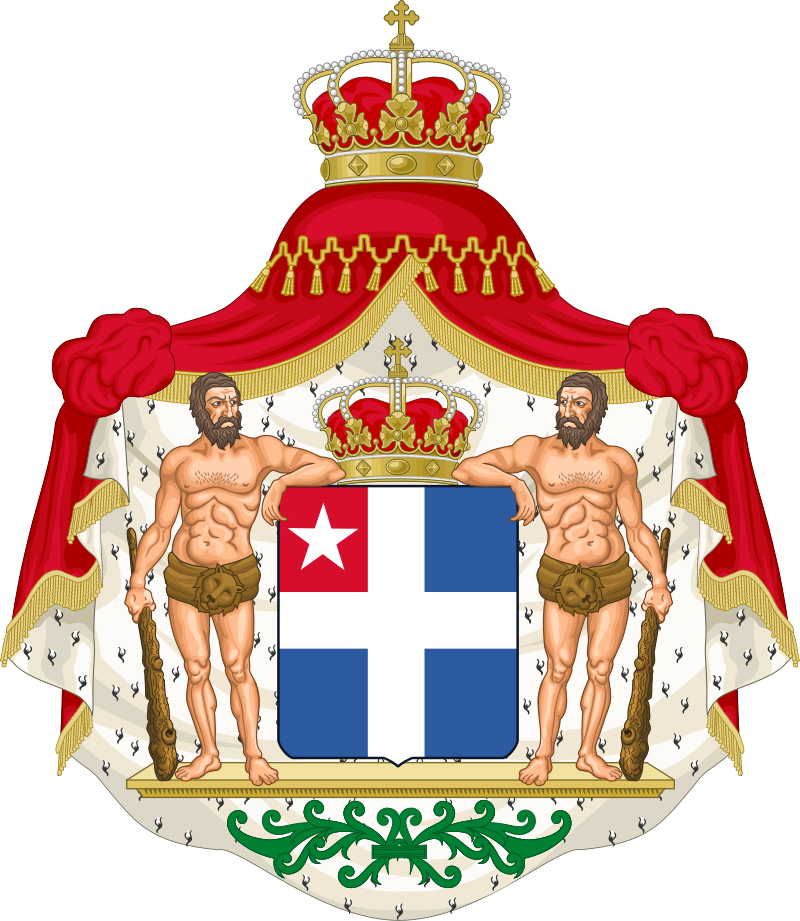

In December 1898, George of Greece assumed the post of High Commissioner. Thus was created a Cretan autonomy under the name “Cretan state” (Greek. Κρητική Πολιτεία, Cretan Politia). In 1899, a government was formed with Eleftherios Venizelos as Minister of Justice.

The island was a state with a reduced autonomy. Prince George really wanted to reunite Crete with Greece. European states agreed with this, however, each country looked at the island from a position of benefit specifically for itself. In 1900, Prince George submitted to the controlling Crete powers a memorandum on the unification of the island with Greece, however, it was rejected by their governments. In response, mass demonstrations of the population for reunification with Greece began in Crete. The Chamber of Deputies of Crete swore allegiance to King George I and decided to replace the Cretan flag raised everywhere with the Greek one. The “Admirals Council” demanded to lower the Greek flags and asked the governments of their countries to send additional ships to the island.

The prince made an unsuccessful effort of reunification confronting the Cretan Minister of Justice, Eleftherios Venizelos, who believed that the unification of Crete with Greece was premature, especially since the Cretan institutions were still unstable. The prince wanted an immediate reunion, so Venizelos was fired. He became the founder of the liberalism movement. The main objectives of his program were the protection of human rights, the establishment of functioning state and the economic recovery of the country. An opposition to Prince George was created.

All these events led to resigning of Prince George as High Commissioner in September 1906 forced by the “Admirals Council”. He was replaced by Alexandros Zaimis, the former Prime Minister of Greece, who later, in 1906, introduced the parliamentary system in Crete. The Italian officers in the gendarmerie were replaced by the Greek ones, the withdrawal of foreign troops from Crete began, as a result of which the island de facto came under Greek control. The withdrawal of international troops was carried out in stages from January 1908 to July 1909.

Voluntary Alliance with Greece

Taking advantage of the Zaimis’ absence, the acting instead of him committee proclaimed in October 1908 the alliance of Crete with Greece; and this decision was subsequently approved by parliament. The post of High Commissioner was abolished and the Greek constitution adopted. Crete unilaterally made a voluntary decision to join the Greek Kingdom; however, the Greek government did not dare to ratify this alliance immediately: this act was not recognized by Greece until October 1912 and until 1913 at the international level—right up to the begin of the Balkan Wars.

In accordance with the London treaty of May 30, 1913, which ended the First Balkan War between the Balkan Union (military-political bloc of Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria) and the Ottoman Empire, the Sultan renounced his official rights to the island. In December, the Greek flag was hoisted above the fortress in Chania, and Crete officially became part of Greece.

Fifteen years of the autonomous Cretan state were marked by a period of development and progress, because government was organized, the Christian population increased and education was qualitatively improved. The flowering of culture took place, which gave the world such masters as philologist Hatzidakis, writers Prevelakis, Nobel Prize winner Elytis and, of course, Kazantzakis.

The Muslim minority of Crete initially remained on the island, but as a result of the defeat of Greece in the Second Greco-Turkish War in 1923, a forced exchange of the population of Greece, Turkey and Bulgaria took place. Muslims from Crete (and other parts of Greece) moved to Turkey, and the Greeks were expelled from Asia Minor to Greece. Some of them came to Crete.

Composed by Victor Dubrovsky