Piracy and Crete

The history of piracy begins almost simultaneously with the history of shipping and trade. Where exactly man began to systematically use sea means, we know – in the Mediterranean Sea long before 3000 BC, when the first surviving vessels were created. This confirms the emergence of a mature culture of unknown origin in Crete around 6000 BC.

What made peaceful and successful merchants turn into pirates? For example, it is known that among Vikings who lived by sea raids, pirate robbery was closely associated with their trade. Successful seafaring, quickness and shelter in an inaccessible place were necessary for the success of sea crimes. Another factor was the rocky homeland and, by this, the preference of the raid economy to the occupation of agriculture. Robbing was a frequent activity of the mountaineers: by the way, it forced Russia to conquer the Caucasus, which mountaineers worried Russian lowlanders with their summer raids; and the Vikings too were mountaineers. The fact, that the mountaineers can be excellent navigators, has long proved in antiquity: for example, the Abkhaz who were once dangerous pirates on the Black Sea. Considering Crete’s agricultural potential, piracy became necessary for its inhabitants as an alternative source of income only after increase of the surplus population. But even it was not the most important. For example, by lacking of land Greeks have been forced to begin the great Greek colonization, and their famous episodic pirate campaign, reflected in world literature, is sailing on the Argo ship “behind the Golden Fleece”.

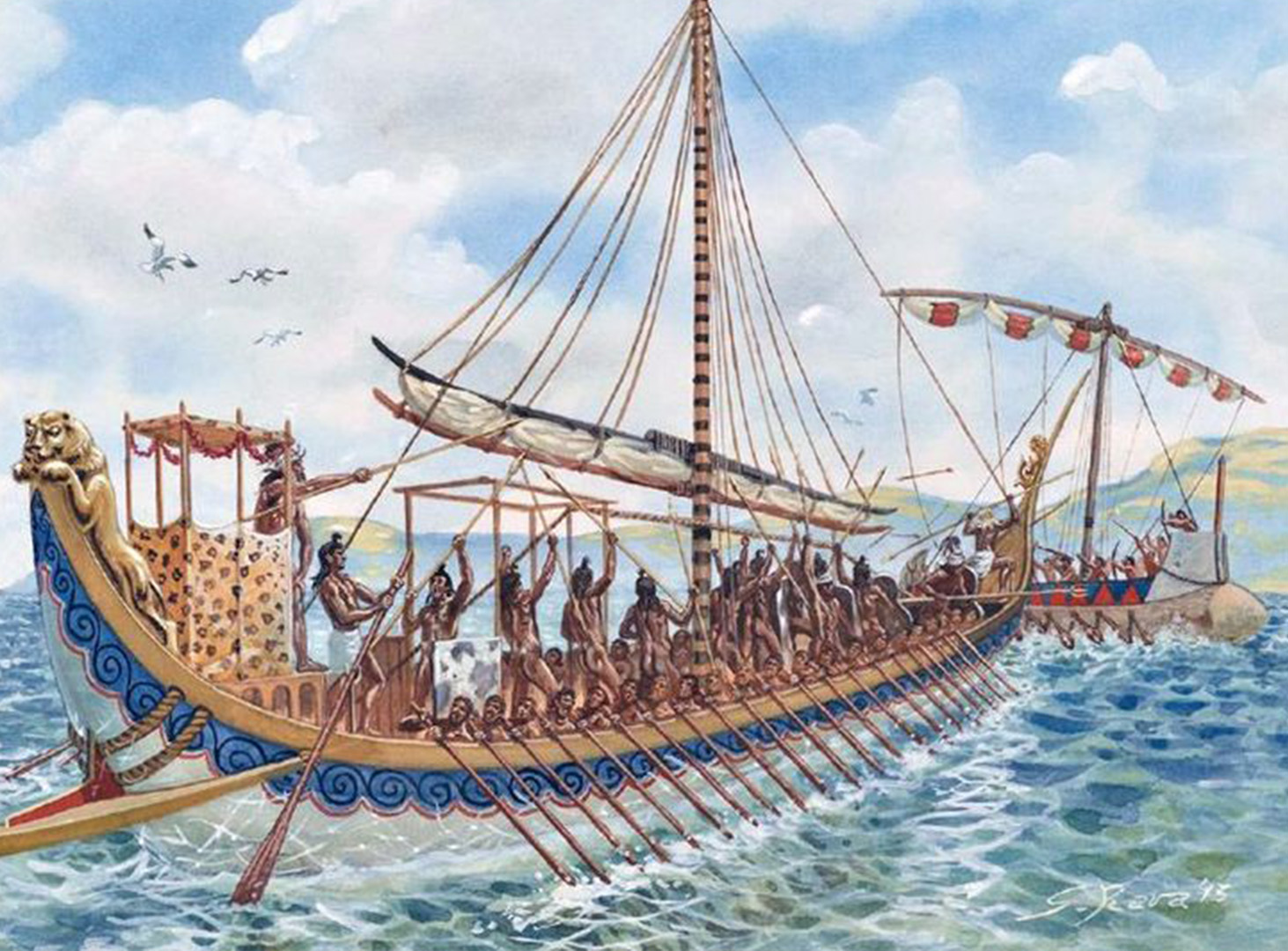

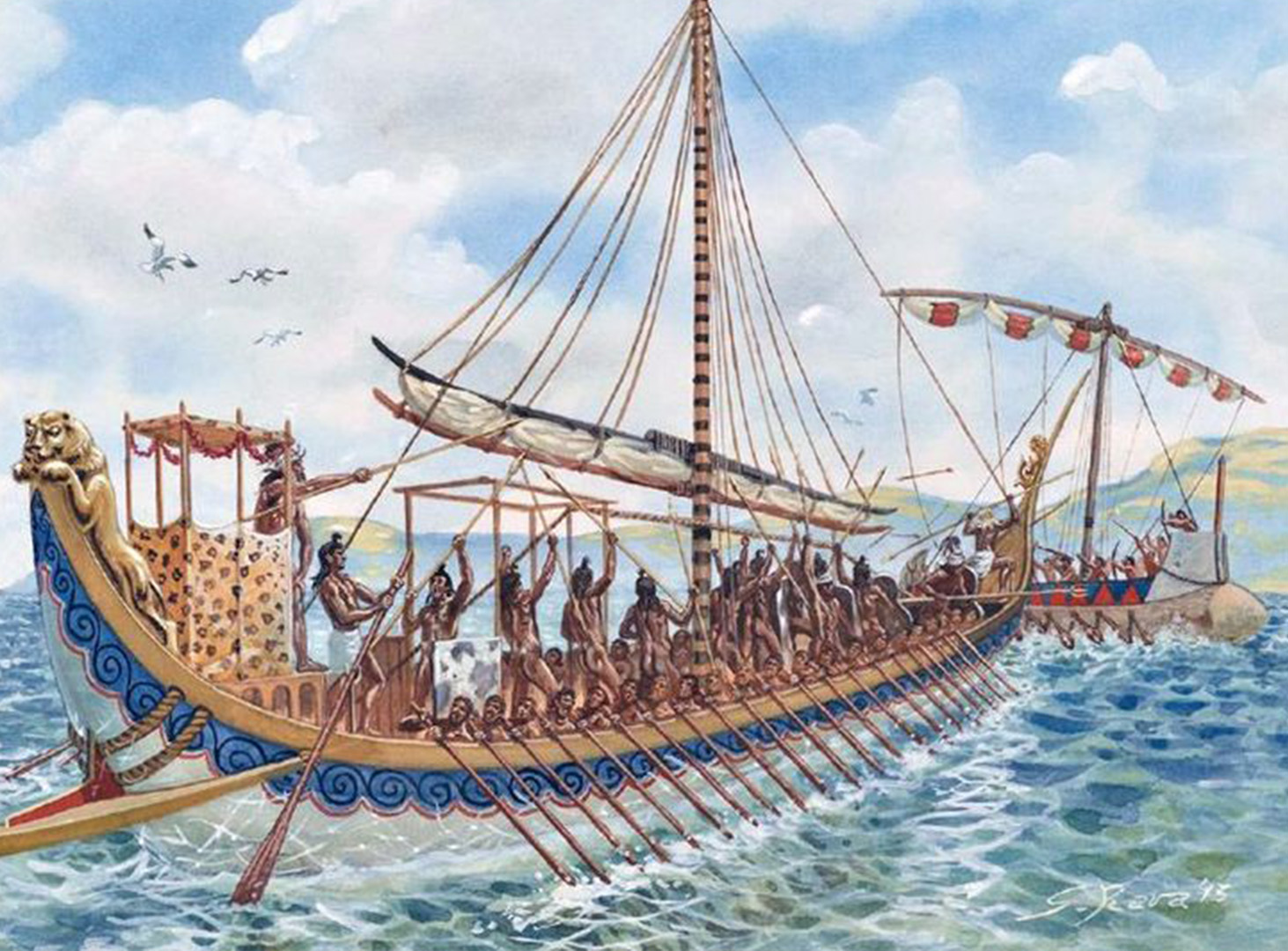

For raiding as the system of the pirates’ economy of the time, coastal navigation was important: sailing along the shores of the inhabitants of Peloponnese, the Balkans, Italy and Asia Minor against which pirate ambushes were made in the rocks of the coast. Other preconditions are the inability of the military fleet to navigate well in the open sea to punish the pirates and the weakness of poleis’ economy, which did not consider the damage caused by pirates as a threat to their well-being.

In addition, even the most sophisticated societies of that time considered livelihoods through robbery one of the 5 main types of human self-sufficiency. They are listed by Aristotle in “Politics” among the natural activities of man: livestock, fishing, hunting, agriculture and predatory life. In ancient Greece piracy was considered a socially acceptable activity that caused reprisals only if it was directed against fellow citizens, and the pirate was often encouraged by local rulers in his work: much later in Europe it lasted until the middle of the XIX century.

Аt night and in poor visibility, the robbers of every kind and just the coastal residents made fires at the reefs, imitating the port, and then robbed the wrecked ships, turning the survivors into slavery. When in the Byzantine Empire under Justinian, a law was passed prohibiting taking away the surviving property from the shipwrecked and converting them into slavery, they simply killed the survivors of the shipwreck so that their property was abandoned. Only in 1111, with the formation of the Hanseatic League of cities, Hamburg entered an alliance with the cities on the coast right up to the Elbe on the prevention of unlawful actions against shipwrecked. Much more could be said about these thieves, but we will return to the pirates of the Mediterranean.

Professionally in ancient times, the Cretans were engaged in piracy: in the first half of the second millennium BC. Minoan Crete dominated the Mediterranean, so that their cities did not even need expensive defensive structures.

Meanwhile, a new predator appeared on the Mediterranean. Diplomacy did not prevent the pharaohs from eagerly looking to the east and not neglecting the riches of the south. At Thutmose III they mastered another direction. In the reliefs on which the nobleman Rehmir glorifies his master, there is a new ethnic type of captives for Egypt. They are hanebu– “the peoples of the islands from the middle of the sea,” the inscription informs. Their clothes are unusual, their tribute is unusual. Only after the excavations in Crete, we can confidently name the location of these islands and at the same time determine the identity of some mysterious objects from Tel-el-Amarna. Trade with Crete ended, as one would expect, with authorized pirate raids.

In the XV century BC, the role of the masters of the Mediterranean passed to the Mycenaean Greeks, who seized Crete around 1400 BC. Documents of the Mycenaean kingdom, referring to the period immediately before the collapse, indicate an increase in piracy and raids to capture slaves, especially from the coast of Asia Minor. In the XIV century BC, the Phoenician pirates made their main bases in Berit, Tire and Sidon–3 fortified cities located along the coast at approximately the same distance from each other. At the same time, piracy flourished on the southern coast of Asia Minor: in it were engaged the Leleges who came to the Peloponnese before the Greeks and lived in the south of the Balkan Peninsula, on Crete, and the Greek Islands of the Aegean Sea as well as in Asia Minor.

Pirates of Lykia (in Asia Minor), who secretly conspired with the king of Cyprus and used the island as a staging post, and refuge, plundered the coast of present-day Syria. Soon after the reign of Ramses II, there were built Egyptian fortresses along the coast of Libya in order to resist sea raids. After collapse of the Mycenaean civilization, there were Tyrrhenians and Thracians who began to pirate in the mass. The island of Lemnos, which had long resisted the Greek colonization, was a haven of Thracian pirates. The Philistines did the same, then the Phoenicians.

In VIII century BC Homer reports on pirates of the Aegean Sea whose coast provided convenient shelters for pirates. Pirates were residents of Sidon (a modern resort in Turkey–nowadays Side), which had its own fleet. There was no tourism, and unsuitable for farming rocky coast was an ideal place for pirate shelters. In addition, the coastal shipping of the time simply favored piracy on small, fast sailboats.

Athenian laws approved a society of pirates and regulated its activities. The pirates were to replenish the fleet of the republic during the war, help the ships of the allies for a fee and patronize maritime trade in peacetime.

States of pirates began to arise on the Aegean and Mediterranean seas. The one of them was the state of Polycrates on Samos, who plundered everyone on the sea, including the inhabitants of the Ionian Islands. Having seized power with the help of his brothers, he took up systematic sea robbery. Creating in a short time a huge fleet of up to 150 ships, he gained complete domination over the Aegean Sea. The Greeks and Phoenicians were forced to pay him tribute to ensure the safety of their ships. Polycrates’ income from piracy was so great that he built a palace on Samos, considered to be one of the 3 wonders of the world which were located on the island. During his time there were built the largest temples and civil buildings. The legend “The Ring of Polycrates” tells about his luckiness. It became allegorical designation of the inevitable tragic end for a happy person.

Incredibly lucky, he was cautioned by his ally Pharaoh Amasis II that lucky people end up badly and recommended him to create for himself failures from time to time, for example, by refusing something the most expensive. On his advice, Polycrates somehow drowned in the sea his beloved precious ring made by skillful stonecutter Mnesarhos, father of mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras. But some time passed, and at a feast they brought him a fish, in which was this ring. The astonished Polycrates wrote about it to Amasis, from whom he received the answer: “The gods are against you–they do not accept your sacrifice. Little misfortune has not befallen you, so expect a big one, and I henceforth break my friendship in order not to be tormented, seeing how my friend suffers, whom I am powerless to help.” It is more likely that the alliance was ended because Polycrates allied with the king Cambyses II against Egypt.

Later, the Persian satrap Oroetus planning to add Samos to Persia’s territory invited him to Magnesia under the pretext of delivering him his treasures, as the king allegedly wants to kill him, and he is searching for refuge. Not trusting the satrap, Polycrates sent his secretary to make sure that there were these treasures. Only after that he went to a meeting in Magnesia despite the prophetic warnings of his daughter who had apparently dreamt of him hanging.

He has been impaled and his dead body was crucified. The latter punishment was a special one of the time for robbers and pirates.

500 years later, the ring of Polycrates was in the collection of the Emperor Augustus where it was already one of the simplest and cheapest. As a result, another legend arose, as if Polycrates had suffered because he wanted to buy off the fate cheaply, after which a saying came up that symbolizes the fatal hopelessness: “There will always be some fish that will bring the Polycrates’ ring”.

To be continued.