Leprosy in Greece: how it was combated

This terrible disease, mentioned in the Bible, mainly affects the skin and then spreads through the body. Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates wrote about it, confusing, probably, with psoriasis.

In the 18th century, this disease has practically disappeared in continental Europe, but in Norway and some areas of Scandinavia was still present, began to spread especially along the coast of Norway in the 19th century; and later – in Iceland. The leprosy seems to have been observed mainly in the western part of Norway and this of course – because of coming foreigners, in connection with Viking campaigns and trade. The first hospital for lepers in Norway was established in Bergen between 1350 and 1400 years. It was the St. Georges Hospital. At the time, this leprosarium was located outside the city. The causative agent of leprosy was discovered in 1873 by the Norwegian physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen, who worked in this oldest European leprosarium in Bergen, where is now the leprosy museum; and lepers were known as Hansenites.

Leprosy was transmitted through discharge from the nose and mouth, during close and frequent contact with people who do not undergo treatment. The group of high-risk morbidity includes residents of areas with endemic leprosy: with poor living conditions, contaminated water, without bedding and enough food. Such conditions have long been absent in Greece.

In general, leprosy is common in tropical countries. In 2000, WHO has reported on the 91 countries with endemic foci of leprosy. India, Burma and Nepal together accounted for 70% of incidence. Meanwhile, as established by British doctors in Europe, some of squirrels living in nature are carriers of the causative agent of human leprosy.

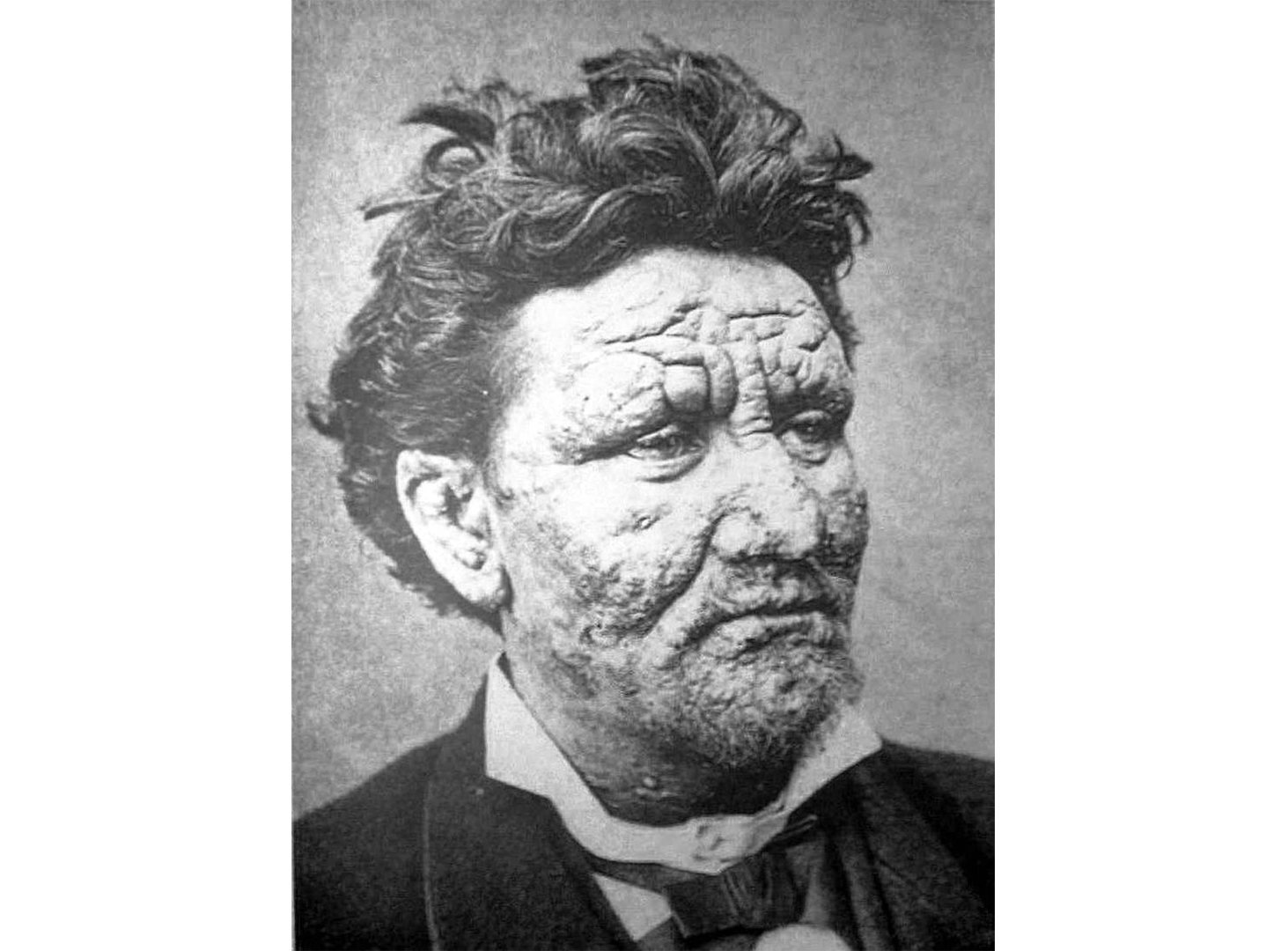

Presumably, in ancient times, Greece was the first Mediterranean country in Europe, infected with leprosy. Apparently, it was brought by the Phoenicians in the middle of the second millennium from the Eastern Mediterranean. The country received new infections during military campaigns of Darius and Xerxes. Then, there were the campaigns of Alexander the Great, the ones of Romans to Assyria, Syria and Egypt, the Crusade campaigns and the invasions of Turkish and Egyptian troops during the war for the independence of Greece. The statistics of 1840 gives 96 cases on the Peloponnesian peninsula and 60 on the Aegean islands. In 1851 there were already 350 cases of diseases. In 1853, Dr. Kigala, studying the situation in Greece, concludes both hereditary and infectious origin of this disease. In April 1882, a native of Lesbos, physician Georgy Karamitsas, who received medical education in Würzburg, makes a report in Athens, where he claims that leprosy has become endemic in some of Greek regions. The less known Greek physician Zambako Pasha in 1897 publishes his fundamental textbook “Leper Peripatetics of Constantinople.”

It is worth telling about Dimitris Zambakos, born in the village of Neochori at Constantinople. Now it’s Yeniköy (exact Turkish translation from Greek, meaning “New Village”), a district of Istanbul. He studied skin and venereal diseases in Paris with Philippe Ricord, one of the founders of venerology. In 1860 he married artist and model Maria-Terpsifea Cassavettis, who broke up with her passionate admirer Georges du Maurier (the grandfather of the British writer Daphne Du Maurier). Being lover of the bohemian way of life and dedicated herself to the art, this daughter of a rich English merchant of Greek descent Demetrius Cassavettis, who inherited his fortune, was very popular among the Pre-Raphaelites, but this marriage was not a happy one: in 1866 she went to live with her mother in London and he, living in Paris, received French citizenship. In 1872 he was invited to Constantinople by the Ottoman ambassador to France and became the personal doctor of Sultan Abdul-Hamid II, from whom he received the title of Pasha (General). In the dispute about the contagiousness of leprosy, he, based on his study of an old foci of leprosy in Skoutari (modern Üsküdar in Istanbul – a bad translation from Greek), expressed the idea of its “hereditary” nature: visiting the island of Chios, he found that leprosy affected 15% of its population and doctors confuse in many cases this disease with syphilis. In 1910, on his recommendation, the first scientific expedition to the Dodecanese islands was carried out to identify leprosy, where it was identified. In 1914, after his death, his major work “Leprosy: Through Centuries and Countries” appeared in French.

Zambakos did not miss the rare opportunity to study eunuchism: the state of the organism that occurs with excessively reduced activity of the sexual glands, therefore, there is an underdevelopment of the genital organs, obesity and disproportion of the skeleton. This is the brightest example of the influence of physiology on behavioral disorders. The eunuchs in the palace of the Emperor of Byzantium, and then in the Sultan’s palace played a significant role, and Zambakos devoted his work to eunuchism, having examined more than two hundred eunuchs from the sultan’s harem. After the restoration of the Constitution in the Ottoman Empire, he began openly condemning the Ottoman trade relations with the “eunuchs’ factories” in Darfur (Sudan) and Ethiopia: at the insistence of the British, the slave trade was banned in the early fifties of the 19th century; continued was only the sale of black eunuchs and Circassians, overflowing the Ottoman Empire after the end of the Caucasian War.

The Turks remember him: on the island of Büyükada (Prinkipo), there is a restored 3-storey wooden palace (kiosk) there.

People were terrified of leprosy and lepers had to wear bells to warn people of their approach. In 1896, the Greek government established a leper colony on the island of Samos, and in August 1904 another one of Saint Panteleimon on the island of Spinalonga (now an interesting and rare attraction in Crete): a leper colony was established on Spinalonga, to isolate lepers from the healthy population. By the Greek law of 1920, the isolation of lepers became mandatory. Throughout the country measures were taken to combat leprosy. In 1930, a hospital for the lepers was opened in Spinalonga: there were 278 patients there–the most of them. 170 people were treated as outpatients in Athens, 76 in Samos, 26 in Chios (in the oldest leper colony in Greece, founded in the middle of the 16th century) and 4 – in the Monastery of Iviron on Mount Athos. Apparently, in the fight against leprosy, Crete played a decisive role: in 1853 in 9 Cretan villages 628 lepers were recorded. On the island of Samos, the disease was brought from Lesbos, along with captured Albanians, who were brought there by order of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

From 1948 onwards, when the cure for this dreadful disease was discovered, the number of lepers in Greece fell and buildings on Spinalonga became an attraction.

Compiled using the text of Christos Evangelou “Leprosy in Greece”