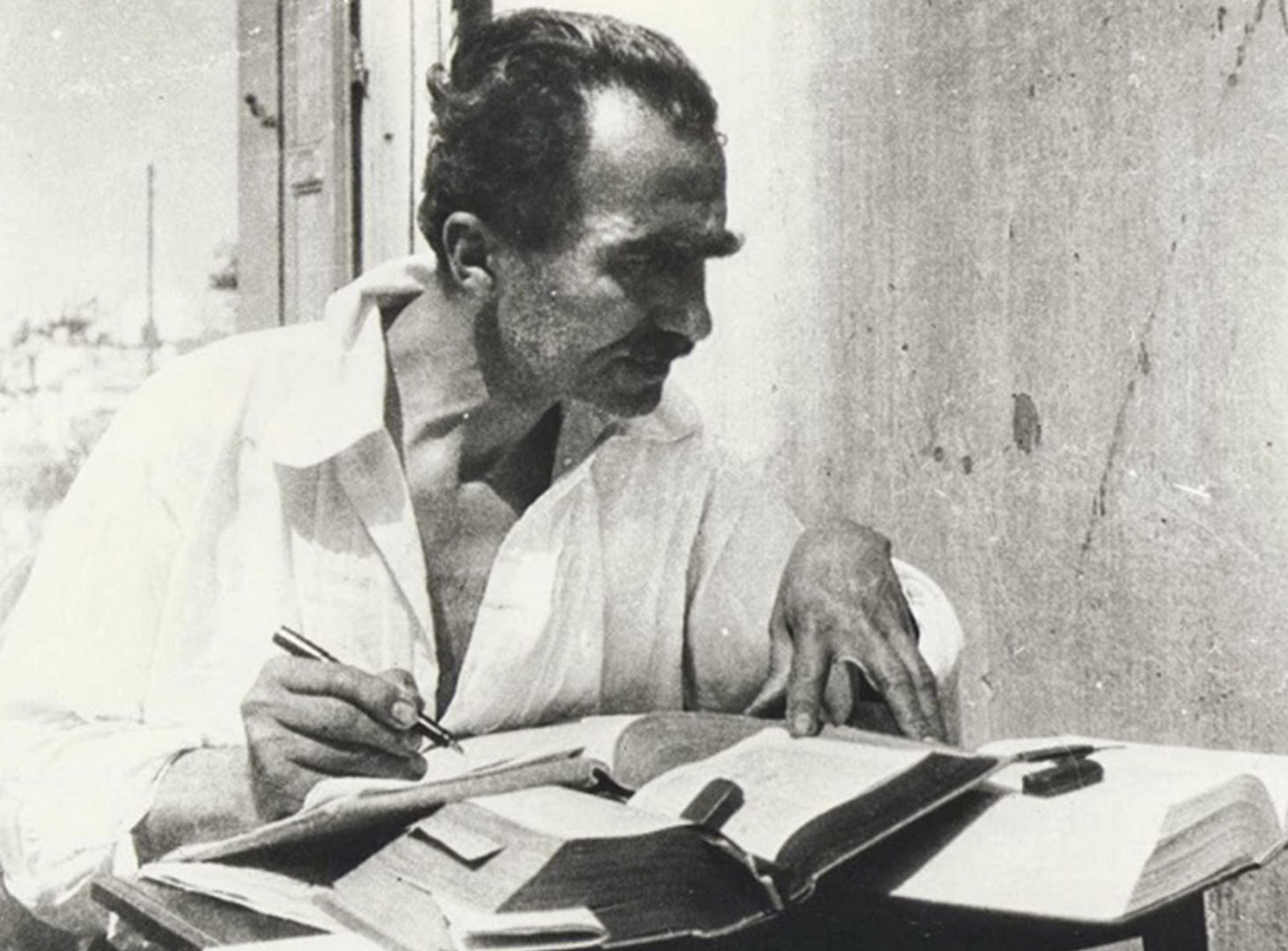

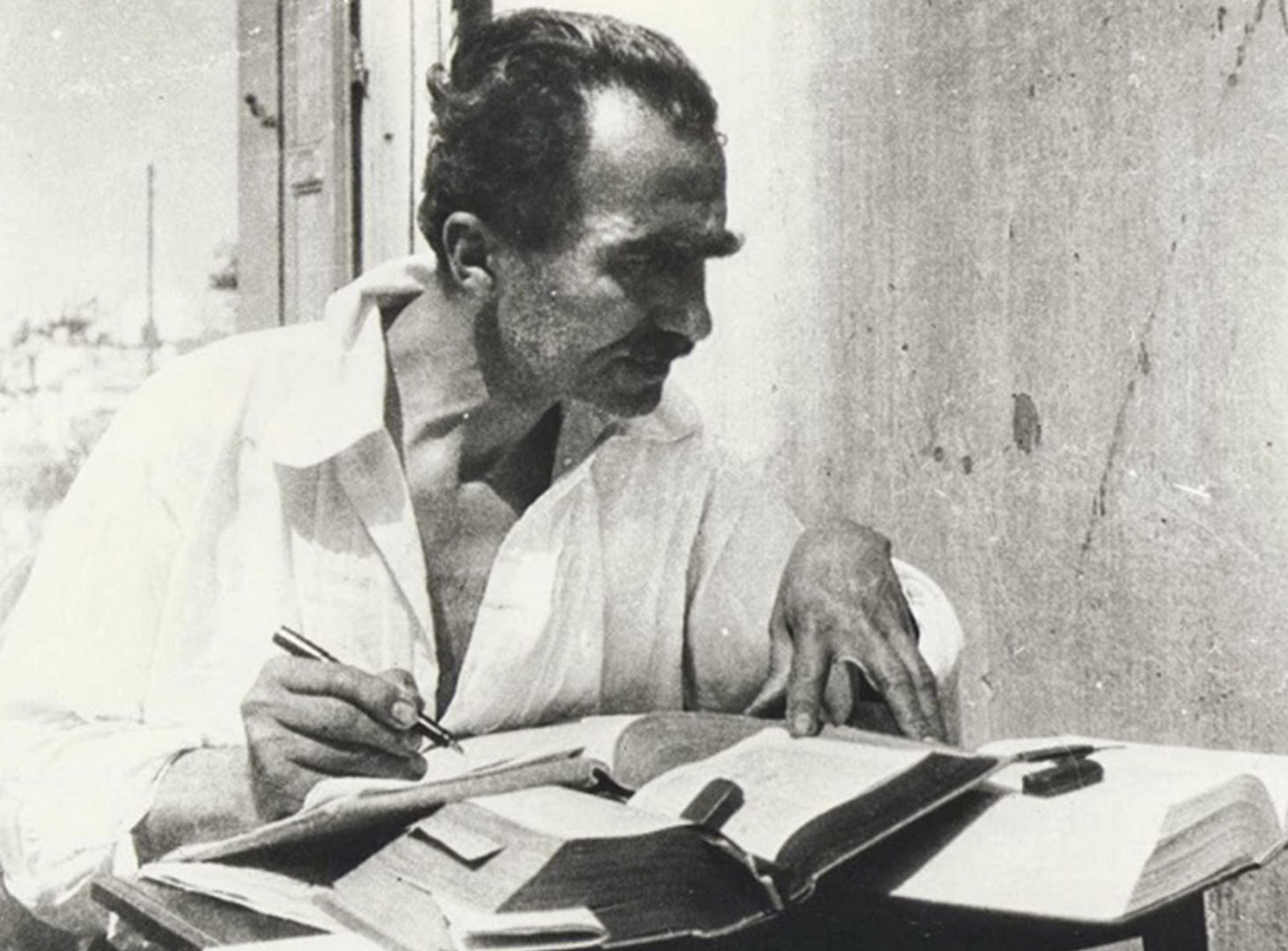

“I hope for nothing. I am not afraid of anything. I am free”

These are the words from the lonely grave of Nikos Kazantzakis buried in Heraklion near one of the old gates of Candia, because the Church refused his burial at a cemetery. Meanwhile at the time he was the world-famous writer thanks to his character―Zorba the Greek.

For Nikos Kazantzakis, the beginning of his world fame was 1964: it was released a film based on his novel The Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas. The author himself considered his Odyssey: a Modern Sequel to be the most important poem. He rewrote it seven times before publishing in 1938. For Kazantzakis, the image of Dante as a poet and creator of the new Italian language was incredibly important. Being writer and international journalist, he was obsessed with doing the same for the Greek language. With this he rewrote his “Odyssey”, but, like all the poetry of Kazantzakis, it remained in the shadow of his best-selling novels. Several times the writer was nominated for the Nobel Prize, and his novel The Last Temptation of Christ made people look differently at the very essence of Christianity. Based on his novel and released in 1988, the Martin Scorsese film “The Last Temptation of Christ” was for many a revelation. The Church saw both the book and the film seditious: in 1954 the Pope added the book to the banned list, and the film was banned in more than a dozen countries, including Turkey, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, the Philippines and Singapore.

Kazantzakis was born on February 18, 1883 in Candia, as Heraklion was formerly called. At that time, Crete was still in the Ottoman Empire, and on the island, there were several rebellions in attempts to join Greece. He himself was a witness once. The family had to leave the island. In 1902 the author moved to Athens to study law, where he published his first story, then in 1907 went to Paris to study philosophy. There, his dissertation was devoted to Nietzsche’s views on state and law. In the German philosopher, he was admired not by the cult of force and the glorification of the superman. He saw both in his books and in his personality―the great tragedy of the human spirit. Kazantzakis himself was in spiritual search all the time.

As a lawyer, he served at the Office of the Greek Prime Minister, and he quickly made a career: in 1919, having received the post of Director General of the Ministry of Social Welfare, he dealt with the problems of repatriating Greek immigrants living in the Caucasus, from where he organized the return of tens of thousands. At that time, he first came to Russia. Among them were the Greeks from Georgian Tsalka, Trialeti and a dozen more villages that fled there from the Pontic settlement of Santa after the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878, because of their help to the Russians. Even in 1989, they still constituted the majority of the population in Tsalka.

A few years ago, I happened to be in that Santa in the Pontic Mountains. The abandoned large agglomeration of the seven nearby villages, which had 16 stone churches at a distance of no more than 100 meters from each other, is shaking even now: 13 of them with collapsed domes are still preserved. The peaceful rural life of the Greeks and Turks, described by Kazantzakis in the novel “Christ Is Crucified Again”, helped mentally restore the paintings of the former wellbeing in this present small village of Dumanlı with rare Turkish summer residents. By the way, Jeremiah Grammatikopoulos, the great-grandfather of our cosmonaut Yurchikhin, was a teacher in this Santa.

Soviet Moscow was for Kazantzakis the New Jerusalem of the working class. In the early 20s he learned Russian and lived there as a special correspondent for the Greek liberal newspaper “Eleutheros Logos” from October 1925 to January 1926. He became closely acquainted with the great “Novo-peasant” poet Klyuev, adherent of mystical holy Russia, whom considered as his teacher Yesenin, “the last poet of village.” Kazantzakis recalled that Lunacharsky’s wife enthusiastically read him verses of Klyuev, who was later banned in the USSR. Rejecting theomachy, soviet anti-religious propaganda, Kazantzakis wrote: “What worries me in Russia is not the reality to which they came, but the reality to which they aspire, not knowing that it is inaccessible.” After traveling around the country and exploring the realities of the communist regime, he was disappointed in it. The contradictions of Russia, the bureaucratization of the Bolshevik regime in the bourgeois manner convinced Kazantzakis of the need to raise the personality over purely material life.

After his satirical attacks against the oppressive atmosphere of Athos, against the distortion of the image of Christ, who was perceived only as a strict Pantocrator, merciless Tsar depicted in gold vestments, Kazantzakis made many enemies in the official Church, and although in 1945 after the liberation of Greece, he spent a year as a Minister, he was forced to leave his homeland. Since 1947 he moved to Western Europe, where he lived until his death. Nevertheless, he always remained a Christian, although until the end of his days he honored Nietzsche, Buddha and Lenin. Of course, his Christianity was far from traditional Orthodoxy and drawing closer to the “theology of liberation”, combining social and humanistic pathos. His Christ fights against poverty and oppression. He is always on the side of the poor and the oppressed.

At the end of his life, Kazantzakis wrote about Christianity and the meaning of human life: “Every person worthy of being called the son of man takes his cross and goes his way to Golgotha. Many, very many reach the first or even the second step and choke, fall exhausted in the middle travels and do not reach the Place of the Skull…”

His death after visiting China became a tragic accident after forced vaccination of plane passengers on the way from China to Japan because of the epidemic of the Asian flu. The drug caused infection, and it was too much for his body, weakened by a long-standing cancer disease. The path of the Christian Nikos Kazantzakis ended on October 26, 1957, in Germany, that is in exile―this was his Golgotha. Billionaire Onassis provided the plane to transport the body, which was accompanied by the widow and former Prime Minister of Greece George Papandreou, but for a place in a Cretan cemetery, glory and power, and money were not enough.

If you want to remember this person, about which everyone arriving on Crete hears: “Nikos Kazantzakis Airport …”, you can go to his resting place―the Martinengo bastion in Heraklion―and learn more about his life in the writer’s museum (the house of Kazantzakis’s father), in the Cretan village of Myrtia, which is 20 km from Heraklion.

Oleg Loginov.